‘The Art of the SCAR’ exhibit details the hidden beauty of organ transplants

A two-day exhibit at the UIHC showcases a 2014 art series that presents scars from organ transplants as works of art and not something to be hidden away.

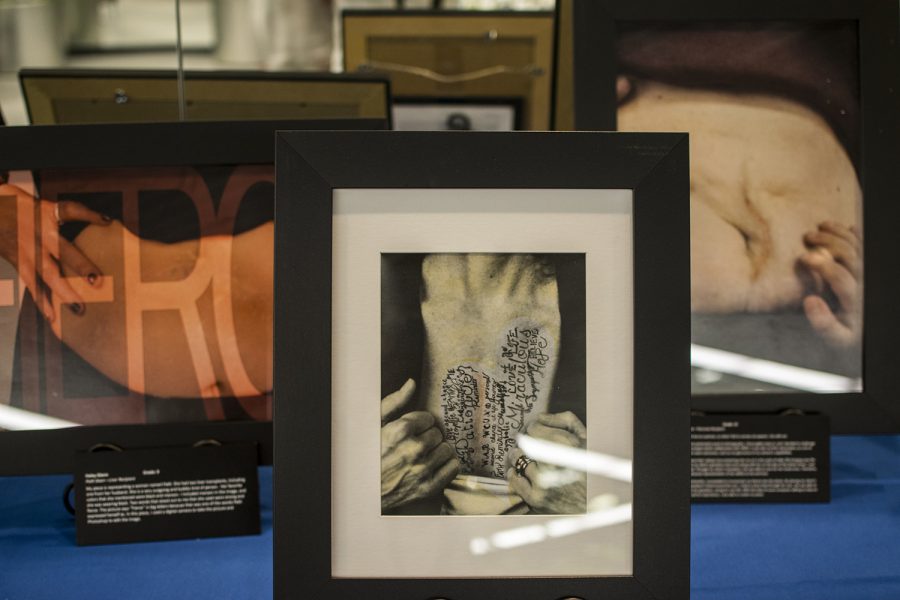

Pictures at the ‘Art of the SCAR’ is seen on Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2018. It is a traveling exhibition starring transplants recipients and living donors.

September 12, 2018

An art exhibit at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics aims to showcase the beauty of surgery scars.

Today, visitors to UIHC can see some of this artwork for themselves.

The exhibit contains 15 of the 37 The Art of the SCAR paintings and portraits made by Clover Hill High School students and teachers in Midlothian, Virginia. The series was made in 2014.

In the series displayed at the UIHC first-floor lobby, visitors can see portraits based on the surgical scars of 10 people who needed heart, liver or, in one instance, double arm transplants. Also included are short descriptions by the creators of each piece of artwork detailing their process behind making the portrait and working with the models.

When it isn’t traveling, the artwork is kept at the United Network for Organ Sharing center in Richmond, Virginia. The organ center holds a national contract to run the American organ transplant network.

“What I hope The Art of the SCAR does is give people pause to think about what patients have to go through, and not just organ transplant patients, but all patients,” said Alan Reed, the chief of transplant at the UIHC Donor Center.

Reed was instrumental in bringing the exhibit to the UIHC. He worked with a pharmaceutical representative from Veloxis to bring the exhibition to the UIHC free of charge.

Members of the UIHC Organ Transplant Center manage patients who need similar surgeries on a regular basis.

“I think it’s quite commendable, because I think in many instances we think of scars as something to hide, when in fact … these patients have fought through their diseases,” said Angie Korsun, the chief administrative officer of the Organ Transplant Center. “They have undergone major surgery, they’re dealing with chronic illnesses and the recovery, and they’re obviously celebrating their second chance at life.”

Some UIHC staff are responsible for providing care to families of loved ones who have died who choose for their organs to be donated.

“We provide that end of life care, bereavement support, and work with [families] on the opportunity that donation is for them,” said Suzanne Witte, clinical manager at the Department of Social Service at the UIHC. “For a lot of our donor families, it’s a chance to take a terrible event and make something good come out of it.”

Witte also works with patients who are not ill. Altruistic donors are healthy people who decide to donate organs out of the goodness of their hearts, she said. After rigorous medical screenings, they undergo surgery to help out strangers.

Out of the pictures of people with scars showcasing their new organs, one of the images in the exhibit shows two men standing next to each other, a donor and recipient, one man who gave a piece of his own body to help out a friend.

“That scar is a symbol of that second chance at life. That scar is not something ugly or something to be hidden,” Korsun said.