A recent study done at the University of Iowa’s State Hygienic Laboratory found high lead levels in blood from 1 in 5 Iowa newborns in a test of more than 2,300 infant blood samples taken from 2006-08.

Donald Simmons, the manager of the Iowa Laboratory Facilities in Ankeny and coauthor of the study, said researchers were approached by Audrey Saftlas, a UI professor emeritus of epidemiology, to conduct the study because there was not a lot of research in the area.

The Hygienic Lab screens newborns for inherited diseases, but these newborn screenings do not normally include routine testing for lead levels.

“When a pregnant woman is exposed to lead, the lead can travel through the placenta into the baby’s blood stream,” Simmons said. “Lead mimics calcium, which plays a role in how your brain communicates, so we can see some drops in IQ and problems in cognition in babies and children with high blood-lead levels.”

RELATED: UI researchers take the load on recent leukemia study

Because lead is similar to calcium, the body stores lead in the bones, meaning it is eliminated very slowly from the system.

“Children are especially vulnerable because this is the time when their brains are developing,” Simmons said.

The results of the study indicated 1 in 5 Iowa newborns’ blood-lead levels exceeded 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood, the action level set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Margaret Carrel, a UI assistant professor of geographical and sustainability sciences, stressed there is no amount of lead in the blood considered safe, but this action level is the point at which treatment should be sought.

“We only had the zip code where the mother lived and the lead level in the baby’s blood,” Carrel said. “The interesting thing is, we found equal numbers of urban and rural children with these levels that exceeded the CDC action level.”

Carrel said people tend to classify this as an urban problem, which could mean those in rural areas do not take precautions as actively as they should.

RELATED: UI program leads nation

“Lead is ubiquitous; it’s everywhere,” Simmons said. “Blood-lead levels have gone down over the years once they removed it from things like paint and gasoline, but if that older paint is exposed in a home, children can still come into contact with lead.”

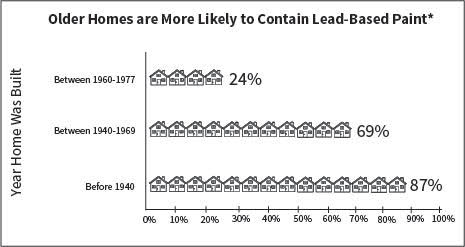

Lead paint is common in pre-1940s housing, but lead exposure can also have many other sources, such as clay pottery, battery plants, and even toys. A study done by Simmons in 2006 found that toys made in China were loaded with lead.

Brian Wels, a Hygienic Lab environmental specialist and coauthor of the study, said another main source of lead is pipes in older housing.

“Even if the lead piping is removed from the house itself, the pipeline to the house that is buried in the street could still be lead,” Wels said.

Carrel said a challenge to solving the issue is that not every person has access to fixing the problem.